Want to freak out your non-medical friends and learn about oddball diagnoses at the same time? Figure 1, my new favorite app, is a crowd-sourced photo app like Instagram that let’s users post photos…of their patients unusual anatomy. It’s a HIPAA violation waiting to happen, but for the meantime, it’s fascinating! One of my personal favorites, user iheartautopsy, recently posted a 20 lb. ovary in addition to prior photos of a brain removal. Needless to say, it’s not for the weak-stomached.

We descend the stairs of our chartered bus into a muddy pit spotted with hairy baby pigs. I carry the portable ultrasound, a bag of chux, and the two pieces of plywood that serve as our stirrups, carefully shimmying through the crowd of women gathered around the door. Most are from the small Guatemalan town we’ve called home for the last week, but several have trekked in on foot from their farms tucked away in the neighboring hills. We watch the earthy lumps from the bus and play a game – Hill or Buried Mayan Pyramid? The women I’m trying not to accidentally smack with the makeshift stirrups probably know. Time spent indulging in archaeological discussions is time better spent seeing another patient.

Like a horny teenage boy I have to talk the women out of their clothes. “Everything?” she asks. “Everything,” I respond. She strips down, leaving only los bloomers. “Those too,” She looks at me with skepticism. “I know it seems odd, but there’s no way to do an exam with those on.” Many of the women have never had a pelvic exam, especially the younger women. Their first will be with a white foreigner in a strange green pajama suit and her Spanish-speaking sidekick: me.

I translate directly the first day, turning the doctor’s English words straight into Spanish. By the time we’re 50 patients in (day 2), we’ve established a routine. “Give her the talk,” the doctor says, and I begin to explain fibroids (benign tumors of the uterus), or how to protect against kidney infections, or that after having 12 children the pelvic organs often begin to descend, even prolapsing out through the vagina (seriously). These are talks I hear her give every workday in the States to American women with the exact same problems. Here, however, we are not armed with a gynecological artillery of birth control pills and pessaries (a device used to hold up pelvic organ prolapse). Our small pharmacy keeps only the necessities. In some cases, the most we can do is reassure that what they’re feeling or seeing or sensing is normal. Until it’s not.

She’s been bleeding for months. She knows. The minute she pulls up her emerald hand-embroidered skirts and the exam begins, I see the doctor’s eyes widen, not in confusion, but in sadness. The doctor asks me to meet her outside of the “room,” which is actually several plastic drapes duct-taped together and slung over a clothesline. I step out. She follows. “This is invasive cervical cancer,” she says, “and she will probably die not long from now.” Then I realize why we’ve stepped out of the breezy blue kludged-together exam room. “You’re going to have to tell her,” she says, knowing full well that I, a recent convert to the medical profession, have never told anyone this before. Now my eyes widen. I breathe deeply, wondering if I will cry, or if she, the patient, will cry, or if we both will cry. Neither of us does. She already knows.

I present her options to her – radical hysterectomy at the national cancer center, which requires a long and expensive trip to Guatemala City. It probably will not save her. She can’t hear me though. I’ve seen the glass-eyed look before. Everything sounds like you’re underwater and the picture starts to blur. So I stop. I walk her out of the cinderblock schoolroom to the desk a few doors down where her care, or lack thereof, will be coordinated. I ask bleakly if I can find any of her relatives to come sit with her. She shakes her head no. I want to hug her so badly, to tell her it will be ok, but I can’t, and it won’t. So I return to the little room we call clinic. We see another patient, and another, yet the line never seems to dwindle.

Being a postbac premed, I constantly ask myself why. Why am I putting myself through the sadomasochism of premedical studies? Why does the third equivalence point in a polyprotic acid titration not follow the same rules as the first two? Why am I dreaming about RLC circuits (there no rest for the weary even in sleep)? One of my most persistent questions has been, why is General Physics part of the premedical curriculum? In two semesters of General Physics, I have learned one thing I can directly relate from curriculum to clinic. And I learned it from Physics for Dummies (it concerned calculating blood pressure in an aneurysm using Bernoulli’s Equation). I can complain at length about how useless this course is for premedical students, what a waste of time and money it is, and how insane it is that there is a class called “Physics of the Human Body” at Columbia, yet we still take General Physics. Yet this kind of self-pity and frustration is counterproductive.

At the start of the semester, I set out on a mission to prove to myself that there was a good reason for me to be taking physics in order to become a physician. Have I proved this yet? No. A working knowledge of physics can be very valuable to a medical education…in that there is an MCAT Physics section. Beyond that, few doctors and medical students I’ve spoken with have actually found the course useful in their practice.

A few gems like the TED talks below have helped me realize how useful physics is for innovation in general. Take Elon Musk, the ultra-brilliant, probably from the future, braingasmic founder of Tesla Motors, PayPal, and SpaceX, who attributes his massive success as an entrepreneur to his study of physics. If the doctors of tomorrow are to take on the future’s advanced medical problems, we must be innovative investigators of the human machine. While calculating the normal force of a block sliding down an inclined plane may not directly teach me how to care for and treat a human being, it did teach me to seek answers invisible to the naked eye.

Below is a story I read for the Columbia Postbac Premed Symposium earlier this year. It’s mostly fact, a little fiction, and a little something in between.

It’s 2007 and I’m sitting in the waiting room of a sperm bank in Memphis with my boyfriend. His parents have sequestered themselves in the Starbucks downstairs in an attempt to reduce the awkwardness inherent in being at a sperm bank with your son. It’s not often that, as a 20-year old woman, you find yourself in a sperm bank, but these were unusual circumstances. My boyfriend Alex had recently been diagnosed with an extremely rare pediatric brain tumor called a pineoblastoma. It had started with skull-crushing headaches, a midnight trip to the ER, the kind of MRI that sets off sirens in every doctor’s head, emergency brain surgery, and then finally, diagnosis and a ratio: 50:50, life or death.

We came to Memphis essentially as recruits to the sickliest, saddest team on the planet. The silver lining of having a super rare brain cancer that only little kids are supposed to get, but you get when you’re 20, is that doctors really want to study you. They will even PAY for your medical treatment to look at the weird little killer cells multiplying faster than tribbles inside your body. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital offered just that. You may have heard of St. Jude from the late night infomercials where little bald children stare at you from the screen, possibly to some Enya or Sarah Maclachlan ballad. It’s a fundraising Goliath and, if you have cancer, this is the Rolls Royce of cancer hospitals. So we pack up and move into the Memphis Ronald McDonald House.

The Ronald McDonald House looks like the inside of a McDonald’s, except without the swirly chairs and the ball pit. It smells of antiseptic and barbeque, but Alex and I, we can hardly complain. It is a free place to live in a town where we know no one. His parents fly cross-country for the important meetings with radiology and for Christmas, when I decorate a lamp with green construction paper and beads because Christmas trees are laden with germs and are thus prohibited from the RonMcDon. The house is furnished mainly with corporate donations, like the Sleep Number beds that sprang leaks years ago, leaving you to wake up as the filling in a giant mattress taco every morning. The walls of the industrial sized kitchen, where I cook our meals with the rest of the “primary caregivers,” are covered in multicolored handprints of patients past – each with a name, a date of birth, and for the unlucky many, the other date of.

Two months into our seven month stay, Alex starts inpatient chemo – dose intensive cyclophosphamide and cisplatin with an amifostine chaser, along with autologous stem cell transplant. Stem cells destined for transplant are laced with the preservative DMSO, which smells EXACTLY like creamed corn when the cells are thawed out, and the scent leaches out of the orifices of transplantees for days after they receive the cells. The first round of chemo goes swimmingly. Alex vomits for about three days straight and looks like the walking dead, but the nurses claim he’s tolerating the protocol quite well. Alex becomes so weak that he can’t balance on his own when standing up to urinate, so I stand next to him, an arm around his back, and hold the liquid void container while he leans on me. Then his blood pressure plummets, his eyes roll skyward, he falls backward into the bed. And then, it happens. I am R. Kelly-ed. I am showered golden, drenched in creamed corn urine. For a split second, I’m speechless, in part because I’ve discovered firsthand that creamed corn urine only smells like creamed corn, it does not taste like creamed corn, and I’m torn between ensuring that Alex has regained consciousness and beelining for the nearest bottle of mouthwash. The liquid void container drops from my hand and I’m bedside, trying to explain to a confused and scared manboy why I look like I’ve gone for a swim in the Mississippi. If the Mississippi was yellow and smelled of creamed corn.

In the intermediate weeks between rounds of chemo, we wait, amusing ourselves in any way we can. He sleeps, I cook. Never with garlic because the smell makes him vomit. He dreams about Subway sandwiches and red bell peppers and the days before he received calories from a giant bag attached to the central line in his chest. I see my own personality mutating, becoming more and more optimistic, goofy, and even playful to counterweigh his personal apocalypse. We listen to nothing but Elliot Smith. I clean everything. The sheets and towels and our clothes are washed every single day. I practically use antibacterial as body lotion. He wears a surgical mask when we leave the Ronald McDonald House; we kiss through the mask. My germs could mean his deathbed. Once a week I take an hour to lie in the course crabgrass to tan on the banks of the muddy Mississippi, letting the present reality pool into droplets and slide off my skin.

So back to the sperm bank. We are there on that day, months before the R.Kelly incident, to freeze a sample of Alex’s sperm in case the impending chemotherapy treatment leaves him infertile. I spend weeks getting him to think of the future, to think that maybe, someday, whether with me or without me, he might want kids of his own, kids that could be impossible if he doesn’t take the initiative to masturbate on command in a clinic in the Memphis suburbs with his parents waiting downstairs. No pressure.

And now, five years later, he calls me to see if I want to meet for coffee after he goes to the fertility clinic to see if that sperm bank in Memphis can finally throw his sample away. Because he’s alive. And he’s healthy. He can’t hide what happened to him; his hairless skull, with its jagged scars, make Frankenstein feel jealous. Illness is ugly, and gross, and indiscriminate. Being in the thick of it, amidst the frontiers of cancer treatment, was akin to being at war. Except all the soldiers are bald little children, and the enemy they fight is their own body. We both bear the scars of this war, but we are incredibly lucky to do so.

I’m sitting at my desk at 11pm on a Friday night drilling problem after problem out of my textbook, like I did last night…and the night before. This is hardly an unusual situation in my life now; it has become my normal. As a woman in her 20s, this might not seem like the ideal place to be, yet somehow I’m content, even happy, to be exactly where I am. Here’s my strategy: when I start missing my old, fun life and let negativity and doubt creep into my thoughts, I watch the video below.

Positive psychology sounds pretty hokey, like science-cum-The-Secret self help mumbojumbo. Nevertheless, after seven-ish months of casually testing it out in my own life, I can earnestly say it has a noticeable effect. What makes sense about the positive psychology approach is studying what is RIGHT with people who thrive, rather than studying what is WRONG with those who do not. Applying this on an individual basis is simple. As Achor suggests, taking a few moments out of each day to focus on what you are grateful for retrains your brain to see what you have in the world already, not what you could have in the future, be it material things or ideas or friends or hearing Geechee Dan serenade you at a subway stop. And exercise, to quote Elle Woods,

Exercise gives you endorphins, endorphins make you happy. Happy people just don’t shoot their husbands.

See? Positive psychology saves lives! Ok, maybe not every day, but you should exercise. Duh. Meditation…I’ve tried for years to meditate and usually wind up sleeping. Achor’s final suggestion, as modified by yours truly, is random or premeditated acts of kindness that are direct and active, as opposed to the impersonal goodness of donating online to your cause of choice. These acts give you a sense that you can have an effect on people, nevermind how big or small.

Can these tenets be applied in a broader medical scope? On the clinical side, it could skirt the borders of paternalism, but it should not be dismissed. On the research side, well, healthy, happy people don’t buy expensive drugs or treatments. Sick (happy or unhappy) people do. Yet as Harvard School of Public Health professor Dr. Laura Kubzansky notes in this article about happiness and reduction of coronary artery disease,

Negative emotions are only one-half of the equation…It looks like there is a benefit of positive mental health that goes beyond the fact that you’re not depressed. What that is is still a mystery. But when we understand the set of processes involved, we will have much more insight into how health works.

According to my smartypants psychology Ph.D. candidate sister, positive psychology is a “major upcoming area in the field.” Its ideas are starting to take hold in medical fields traditionally confined to studying why sick people are sick, not why healthy people are healthy. As I navigate the landscape of medical education, I know I’ll take the principles of positive psychology I’ve tested on myself with me wherever I go. Why? Because they work.

This fascinating article and video by Gautam Naik for the Wall Street Journal tracks the recent developments in bioengineered organs, aka “replacement parts for the human body.” Whenever the discussion of artificial organs arises, it is important to differentiate between organs that can be harvested from donors vs. those that cannot. Why? Because public policy can essentially dictate the availability of those organs to patients in need. Imagine if, when you went to the DMV to renew your license, you were required to choose whether or not to become an organ donor. This model, called mandated choice, has support from the American Medical Association and has been rehashed and researched by the likes of Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their ode to libertarian paternalism, Nudge.

At a recent Columbia Postbac Premed Surgery Club event, liver and kidney transplant surgeon Dr. Susan Lerner noted her frustrations with the lack of available organs in New York City and the troubled methodology of equitably distributing the available organs. The sickest patients get the available livers, yet the sicker they are, the more difficult (if not impossible) the recovery. A statewide mandated choice model would undoubtedly increase the number of organs available to transplant surgeons like Dr. Lerner.

Changes to organ donation policy look increasingly attractive when one confronts the price tag on bioengineered organs. For organs that cannot be transplanted from donors, the investment is appropriate. For those that can, the mandated choice model is a far more reasonable and cost-effective approach – though it’s certainly not as cool.

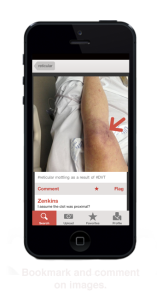

Yesterday, the New York Times ran this piece about Dr. Jay Parkinson, the founder of Sherpaa. Sherpaa functions somewhat like a virtual triage center manned by doctors sick of the medical status quo. If you have an illness, ache, pain, rash, burn or really any health issue, the staff at Sherpaa will direct you to the appropriate means of treatment, provided your employer pays the $50/month per employee charge. If the condition can be treated without an in-person, nonvirtual, visit to a doctor, the doctors at Sherpaa will provide the means to do so. The neat thing is that they’ve caught up to the rest of the industrialized world and will treat patients via text message and email. The more iPhone photos of that weird mole on your arm, the better.

In terms of actually providing healthcare, it’s unclear from the Sherpaa website and the NYT article how the work their doctors do differs from that of underpaid triage nurses in nearly every medical clinic across the country.

A zillion questions came up when I read this article. What is the protocol when an actual emergency occurs? How do they get paid? How does their malpractice insurance differ from that of an established clinic? How do they insure patient confidentiality and adherence to HIPAA? All of these questions will be answered…if they answer my email.

Regardless, the most important take away from Sherpaa and its recent publicity is that healthcare is ripe for change; almost anything is better than what we have now. It takes the pioneering efforts of people like Dr. Parkinson to put their careers on the line and voyage into unknown territory. So thanks, Dr. Parkinson, for taking a snide Gawker article and transforming it into a healthcare model that could have lasting effects on the industry.

Last night, a resident stopped me and asked if I would like to shadow her. I’ve shadowed many of the attending physicians, residents, and nurse practitioners in the ER before, but today was different. She saw patient after patient after patient in order of their arrival. She ordered bloodwork and pertinent scans. She painstakingly recorded each patient’s treatment in the hospital’s gruelingly insufficient electronic medical records system. She couldn’t find a patient’s nurse and was chewed out (jokingly) after forgetting to tell said nurse that the patient moved to the dialysis center (the disappearing patient act). She completed each banal, yet important step in her patients’ care with ease and good humor.

What was unusual about this resident was her interaction with her patients. Each exam was a true dialogue between her and her patient – a verbal dialogue between her and the patient, and a nonverbal dialogue between her and the patient’s body. Abraham Verghese has spoken extensively about the value of “a doctor’s touch,” the hands-on examination of a patient, regardless of whether it is crucial to their forthcoming diagnosis or not. It is about the intimate relationship of trust and security between the doctor and patient, a relationship that is, more often than not, completely lost in the faceless realm of emergency medicine. This resident, who was as pressed for time as all her colleagues, successfully achieved this relationship with nearly every patient she examined. They felt cared for. This should not be an unusual experience.

The ER is a tough place for anyone to work. Some might argue (as a resident on an emergency medicine panel discussion I attended did last week) that jadedness is a prerequisite to becoming an ER doc, that you can’t survive the quotidian trauma without acquiring a certain level of numbness. It is self-preservation. Yet seeing the resident examining today’s patients is proof to me that these truths can coexist. It is possible to cultivate the art of doctoring, to make a patient feel cared for, while working in the high stress, high stakes realm of the emergency department. This resident, the hands-on examiner and compassionate multi-tasker, is the kind of doctor I admire.

Welcome to the Lockative Case! As the tagline suggests, the Lockative Case is a place for discussion of healthcare and humanity, and the plethora of topics in between. My contributions are influenced by the subjects I tackle in day-to-day life as a postbac-premed, in addition to past and present encounters with healthcare. Please feel free to leave comments and/or questions.